Climber Breaks From Team, Attempts and Abandons Solo Ascent of ‘Savage Mountain’

As the world watched the end of the Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang, a different sort of athletic drama unfolded on the planet’s second-highest mountain. For the last eight weeks, a team of Polish alpinists has battled some of the most powerful forces in nature in an attempt to achieve what many in the mountaineering community have long believed impossible: a winter ascent of K2, the crown jewel of the Karakoram Range.

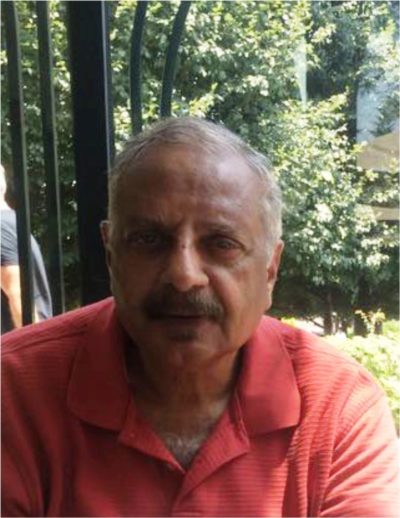

But the story took an unexpected turn at the team’s base camp over the weekend, when Denis Urubko, their strongest climber, abruptly announced he wanted to go for the summit two weeks earlier than team leader Krzysztof Wielicki had planned. An angry argument ensued. Urubko packed his gear and set off alone up the icy, windswept mountain.

He refused to take a radio with him, so the group had no way of contacting him. That Sunday morning, they were unsure where he was on the peak.

“What Denis has done is very selfish,” said Wielicki, when I reached him by satellite phone as I have done regularly over the last several weeks. “Denis thinks it’s all about just him, but it’s not. He has put all of us in danger. If something goes wrong, of course we must try to rescue him.”

By Monday morning, he had abandoned his attempt and was on his way back to base camp. It was later announced on the team’s official Facebook page that he was leaving the expedition.

It’s difficult to explain why anyone would want to climb in the Karakoram during winter, a time when some of the world’s tallest mountains are transformed into an otherworldly arena. Hurricane-force winds regularly strafe their jagged contours armored in hard gray ice, and temperatures plummet to -80°F, lower than the average temperature on Mars.

Rising along the borders of Pakistan, China, and India, these monstrous peaks—which dwarf the Rockies—have little tolerance for humans in any season, but especially in winter. They envelope climbers in blizzards, bury them in avalanches, freeze their blood, and snap their bones. Such brutal conditions have sent most mountaineers home to wait for summer—the traditional Karakoram climbing season. But not Krzysztof Wielicki.

MEET THE MOUNTAIN MAN IN CHARGE

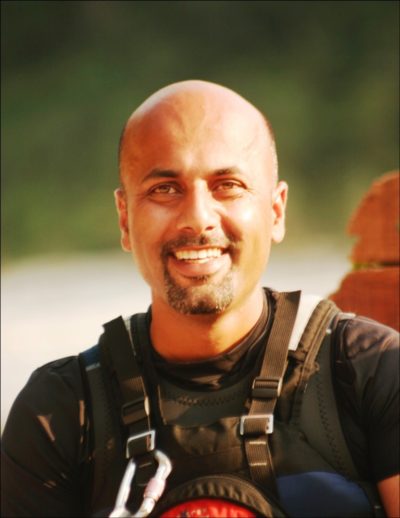

Wielicki, 68, is an old-school Polish alpinist. He believes winter is the true test for high-altitude mountaineers, and K2, which is steeper and deadlier than Mount Everest, is its ultimate achievement.

That same year, the Poles performed poorly in the Winter Olympics, and Wielicki’s climb helped soothe the disappointment of his country. “I realized then,” he told me several years ago, “my mission in life was to help the Polish become the greatest winter climbers in the world,”

He set his sights on the planet’s 13 next tallest mountains, all higher than 8,000 meters (26,246 feet). In 1986, Wielicki and Polish alpinist Jerzy Kukuczka made the first winter ascent of Kangchenjunga, the world’s third-highest mountain. In 1988, this time going solo, Wielicki accomplished the first winter ascent of Lhotse, the fourth-highest. Other Polish teams claimed Cho Oyu, Dhaulagiri I, Manaslu, and Anna Purna, earning Polish mountaineers the nickname the “Ice Warriors.

A TEAM OF THE YOUNG, ANGRY, AND AMBITIOUS

In 2002 Wielicki published his now-famous Winter Manifesto, an essay calling on the next generation of Polish Ice Warriors, asking “the young, angry and ambitious,” to return to the attack and “finish the job.”

It took a decade, but a new wave of Polish winter alpinists did develop and began claiming 8,000-meter winter firsts. Adam Bielecki and Janusz Golab made the first winter ascent of Gasherbrum 1 in 2012, and the following year, Artur Malek was a member of the team that made the first winter ascent of Broad Peak. All three of these climbers are now on K2 with Wielicki.

To date, according to Eberhard Jurgalski, who runs 8000ers.com and tracks climbing statistics, only 31 people have summited an eight-thousander in winter. Fourteen of them are Poles. And Polish climbers have recorded winter ascents on ten of the world’s fourteen 8,000-meter peaks.

A MAD CHALLENGE

The last remaining prize in this rarefied category is K2, a mountain unlike any other. At 28,251 feet, it is roughly 800 feet lower than Everest, but it is much steeper and requires a far greater degree of technical skill to climb under the best conditions.

Adam Bielecki, one of the Polish team’s strongest climbers, fixes ropes on the route to Camp 2. His teammates and he will use these lines to move between camps as they prepare for the final summit push.

PHOTOGRAPH BY DENIS URUBKO

Eighty-four climbers have died attempting to climb K2, and only 306 have reached its summit, giving it a fatality-success ratio of roughly one death for every three summits. By comparison, almost 5,000 people have now summited Everest (more than 8,000 summits if you include climbers who’ve done it more than once), with 288 deaths—one death for every 25 summits. Therefore, K2 is statistically 10 times more dangerous than Everest. And that’s if you try it in summer.

There have been other winter attempts. In 1987-88, Wielicki was part of a 24-man Polish-Canadian-British team. He and Leszek Cichy reached 7,300 meters before high winds and teammates suffering from frostbite forced them to turn around.

In 2002-03, he returned with an international team of Poles, Kazakhs, Uzbeks, and Georgians. The team was able to establish a camp at 7,650 meters, but high winds destroyed it, and one of the climbers developed cerebral edema—swelling of the brain caused by high altitude—and had to be evacuated.

In 2011-12, a Russian team made it to 7,000 meters, but the expedition ended when one of the climbers died of pneumonia and cardiac arrest. Since then, no one has returned in winter—until this year.

Left: Bielecki, who was on the 2012 team that made the first winter ascent of Gasherbrum 1, navigates a steep face on the way to Camp 2 on the Cesen Spur route. The team later abandoned the Cesen Spur because of rock fall.

Right:Artur Malek makes his way along the fixed ropes from Camp 1 to Camp 2.

Wielicki and his team were undeterred by these previous failures. Theybegan this year’s expedition after Christmas in northeast Pakistan, trekking some 60 miles through mountain valleys choked with several feet of snow. They established their base camp on the Godwin-Austen Glacier, which at 5,000 meters (16,400 feet) is higher than Mount Whitney, the tallest peak in the continental United States.

Since then, things have not gone smoothly.

A DRAMATIC RESCUE

Some two weeks after they established their base camp, the team was called to rescue Tomasz Mackiewicz, a fellow Polish mountaineer, and Elisabeth Revol, his French partner, as they tried to summit their own eight-thousander, Nanga Parbat (26,660 feet). The Poles put their expedition on hold without hesitation to come to the aid of other climbers more than 100 miles away.

“We did what we should do,” Wielicki told me after four members of his team had returned to their K2 base camp via a Pakistani military helicopter. “This is the code of the mountains.”

Once the rescue team reached the Nanga Parbat base camp, Denis Urubko and Adam Bielecki—the team’s two strongest climbers—attempted the rescue. The pair rapidly ascended 4,000 feet in the dark to reach her—a startling feat of endurance and skill.

Miraculously, Revol heard them shouting her name, and they were able to find her and get her safely down. Tragically, they were not able to reach her partner Mackiewicz, a climber well known to the K2 team.

A Pakistani military helicopter lands at the team’s base camp to pick up Rafal Fronia, whose arm was fractured by falling rock.

PHOTOGRAPH BY MAREK CHMIELARSKI

DANGER ON THE MOUNTAIN

Ultimately, the wind will determine whether or not a summit is successful. On several days, the team has seen winds reach 50 miles an hour. This creates multiple threats, including dropping the wind chill far below zero—which can quickly cause frostbite—and can blow a climber completely off the mountain, even one who is tied to a rope.

In 1995, high winds plucked famous British climber Alison Hargreaves and five of her teammates, all roped together, right off K2, sending them all to their deaths. And that was in August. Winter brings even stronger winds as the jet stream shifts so that it runs almost directly over the mountain.

The high winds also can send loose rocks hurtling down the mountain’s flanks. In separate incidents, two of Wielicki’s climbers were hit by falling rock. On February 2nd, Bielecki was struck in the face, suffering a broken nose and a gash requiring six stiches. Then Rafal Fronia was hit in the arm by a falling rock, fracturing the bones in his forearm. He was evacuated and is now back in Poland.

“The mountain is dry and the rock fall is bad up to Camp 1,” Wielicki told me, noting that the lack of snow to hold rocks in place made the danger worse. In the background I could hear the wind whipping the walls of his nylon tent. Fist size rocks were randomly whizzing down the wall. “It just became too dangerous to continue,” Wielicki explained.

In response, the team switched the route they’d planned to take up the mountain. They abandoned the Cesen Spur, a shorter, steeper line, in favor of the Abruzzi Ridge, a longer route but better protected from rock fall.

Left: Bielecki approaches the Black Pyramid, one of the most technically demanding features climbers will face as they move up the Abruzzi Ridge between Camp 2 and Camp 3.

Right: Artur Malek descends the mountain on the Cesen Spur.

LAYING SIEGE TO THE MOUNTAIN

Wielicki’s favored approach to winter expeditions is to use “siege” tactics, assiduously erecting a series of three or four tiny camps at various points on the mountain to give the climbers just enough shelter to warm themselves, rest, and eat before moving up. All the camps are connected by ropes anchored to cracks in the rock and ice. These “fixed lines” allow the climbers and porters to move more easily between them.

But high-altitude mountain climbing isn’t just about going up. The climbers must adjust to the whisper thin air (especially Wielicki’s team which is not using bottled oxygen), so they go up the ropes to Camp 1, spend a few nights, then come back down to base camp and recuperate for a few days. On the next foray, they go higher to Camp 2, spend a few nights, then descend back to base camp. This up-and-down process continues over a month, allowing their bodies to adjust.

After the team finally establishes Camp 4, they wait for the next good weather window and the climbers who feel strongest will attempt to make the summit.

After switching routes, the team and their high-altitude porters (local Pakistanis who assist teams in the Karakoram like Nepal’s Sherpas do on Everest) had to remove all the ropes, tents, ice screws, and other equipment from the Cesen Spur and establish the new route up the Abruzzi Ridge.

Bielecki rests inside his Camp 3 tent, perched on tiny ledge at 7,200 meters (23,620 feet) on the frozen slopes of K2. He and the others use the camps to acclimatize to the extreme altitude and to recharge between arduous climbs.

PHOTOGRAPH BY DENIS URUBKO

PREPARING FOR A WINDOW

After the new route on the Abruzzi Ridge was established, Bielecki and Urubko spent their second night at Camp 3, acclimatizing to the thin air. Meanwhile, other members of the team had made it to Camp 1.

The team was making great progress, Wielicki told me last week, and was “physically and mentally ready for this mountain. Absolutely.”

Then came Urubko’s stunning decision to go it alone.

On Friday night, he asked Adam Bielecki, the team’s second strongest member, to join him. He said he wanted to attempt the summit before February 28, which in some mountaineering circles is considered the end of winter rather than March 20, the official meteorological definition.

Bielecki refused, telling Urubko that neither he nor the team was ready to go and that they should remain united and stick to the plan. Urubko became enraged, left the team tent, and stomped out into the snow. On Saturday morning after breakfast, he headed up the mountain alone.

“I don’t understand him,” Wielicki told me, the distress obvious in his voice. “Our plan was for the team to attack the summit in the first part of March.”

Two climbers who do understand Urubko are not surprised. Simone Moro and Cory Richards made the first winter ascent of the 8,035-meter Gasherbrum II with him in 2011.

In December, before the Polish team set out, Moro, who for more than a decade climbed and clashed with Urubko, was asked about the team’s chances and how Urubko, who is Russian by birth but has Polish citizenship, would fare under Wielicki’s leadership.

“He has a Russian military mentality,” Moro said. “He is very strong and he has no fear. These are excellent qualities, but he has to be managed properly to prevent him taking stupid or fatal risks.”

Richards sees it a bit differently. “Denis is very headstrong. He has fairly strong beliefs about how things should be done and his own capacity for fulfilling those things. But look at his climbing resume. He’s by far one of the strongest climbers in the 8,000-meter game.”

“Denis is trying to thread a needle he sees, and he has more experience than anyone on the team.”

Whatever Urubko’s motivation, Wielicki prepared the team to support him. He sent climbers to follow Urubko and be ready at the upper camps to aid him. Luckily, there was no need for a rescue. On Monday morning, Maciej Bedrekczuk and Marcin Kaczkan spotted him on his way back down the mountain.

“We don’t know why he turned around,” said Wielicki, “but it is great news. The weather is turning bad again, snow and strong winds high on the mountain, and we were extremely afraid for his safety.”

After his return, the team announced that Urubko will be leaving the expedition. Without him, the climbers are continuing to plan for their summit. They’re patiently waiting for the right moment, which, according to meteorological reports, may be in the next week.

“The forecast, at least right now, predicts the next weather window will be March 3 through March 6,” Wielicki said excitedly. “Our team will be ready and we will strike for the summit!”

Source : https://www.nationalgeographic.com/adventure/features/athletes/k2-climber-first-winter-summit-attempt-solo/